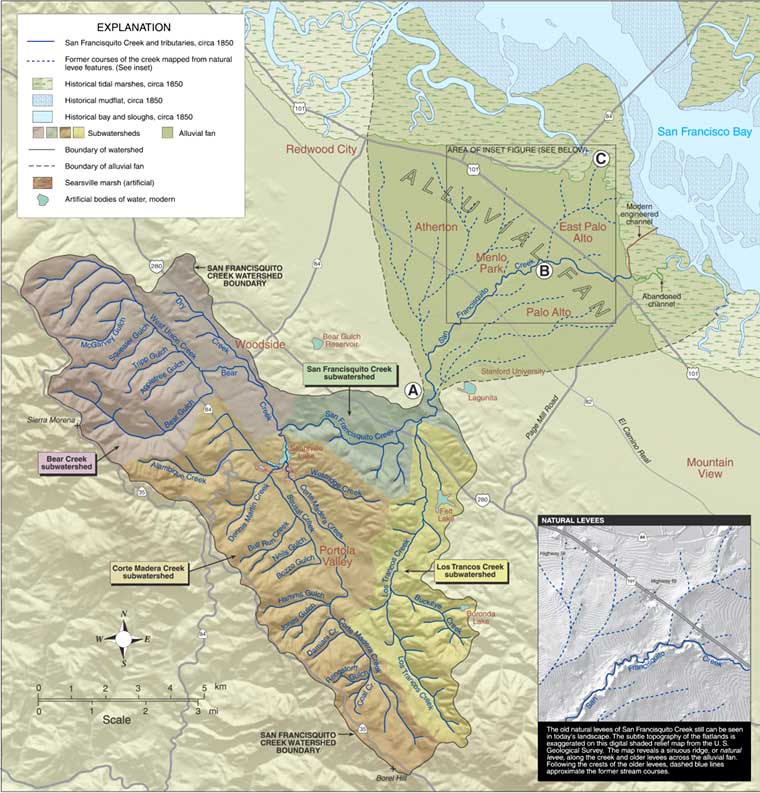

Guide to San Francisco Bay Area CreeksSan Francisquito Watershed & Alluvial Fan

|

Upper Watershed Delivers Water and Sediment During winter storms, the upper watershed funnels water and sediment into San Francisquito Creek. Starting as rain falling on the hillsides, the water flows downhill, then downstream, picking up sediment. The muddy water courses down tributary streams, often eroding bed and bank, until emptying into San Francisquito Creek and rushing toward the flatlands. The Creek Builds the Alluvial Fan The fan now comprises thick deposits of sand and gravel. Creek water easily permeates these porous sediments; San Francisquito Creek loses significant flow into the alluvial deposits. Many smaller neighboring creeks flowing on to alluvial fans historically never reached the bay, but spread out on the flatlands and sank in. Water lost this way ultimately reaches the bay as groundwater. Starting a few thousand years ago, tectonic uplift of the Stanford area caused San Francisquito Creek to gradually abandon the upper portion of its fan and deposit its sediments farther and farther downstream. Incision of the creek channel into the older sediments near the upstream end of the fan confined the creek to a deep channel. Downstream, however, the creek continued to build its alluvial fan. The portion of the fan that East Palo Alto now occupies dates from a time when the creek splayed out near point B. At present San Francisquito Creek is limited from much further fan building. Incision and flood control projects keep the creek from overflowing its banks in all but major floods. In addition, Searsville Lake traps the sediment from the Corte Madera subwatershed, significantly decreasing the material available for fan building. The creek now deposits relatively small amounts of sediment within the channel downstream of point B, and is building a small delta into the bay at the mouth of the 1930s-era engineered channel. Natural Levees Give Shape to the Fan Clues to Where the Creek Once Flowed These former stream courses and their deposits range in age from very recent to a few tens of thousands of years old, with the most recent deposits found downslope of point B. Historical maps of East Palo Alto show an abandoned stream channel still visible along the crest of the northernmost levee. Point C near historic Ravenswood is the protrusion of that levee into the tidal marsh. The subtle levee topography on the San Francisquito alluvial fan has influenced the distribution of vegetation types and patterns of flooding. Historical maps show willows and wetlands occupying the low areas between levees, especially near the bay shore, and live oak and laurel occupying the levees. In the 1998 flood, the largest of record for San Francisquito Creek, water spilled out of the channel and flooded the low-lying areas between the levees, leaving the levee areas dry. Alluvial Fans in an Urban Setting The natural processes of erosion and sedimentation are also problems in an

urban setting. Sediment can choke the lower portions of stream channels on alluvial

fans, diminishing their flood capacity. Dredging can deepen the channel to prevent

flooding. Alternatively, levees can be built or raised along the creek bank. Upstream

reaches erode naturally, and measures are often taken to protect creekside property,

such as reinforcing the banks or moving structures away from the creek. |

Top of PageSan Francisquito Watershed InformationGlossary |