Giant Gold Machines - Hydraulic MiningAn

ancient northern California river once laid down an immense bed of gold-bearing gravel.

There had to be an easy way of getting down to the ancient streambeds now buried in the

mountains. There was: hydraulic mining.

Click here to see

Malakoff Diggins

Click icon to hear

Hydraulic Mining

Water

was diverted into ditches and wooden flumes at high elevations, and gravity did the rest.

Channeled through heavy iron pipes, the water exploded from a nozzle far below with a

force of 5000 pounds. This giant hydraulic monitor looks like a cannon. No wonder. It's a

water cannon, and it could blast the mountains to smithereens, leaving huge craters. It

was very efficient at getting to the gold. The first monitors were small, with canvas

hoses. Then miners decided bigger is better. This thirteen-foot monitor, made by the

Empire Foundry in Marysville in the 1870s, is not even the biggest. Imagine a monitor

sixteen to eighteen feet long, blasting a stream of water four hundred to five hundred

feet, like was used at Malakoff Diggings. Water

was diverted into ditches and wooden flumes at high elevations, and gravity did the rest.

Channeled through heavy iron pipes, the water exploded from a nozzle far below with a

force of 5000 pounds. This giant hydraulic monitor looks like a cannon. No wonder. It's a

water cannon, and it could blast the mountains to smithereens, leaving huge craters. It

was very efficient at getting to the gold. The first monitors were small, with canvas

hoses. Then miners decided bigger is better. This thirteen-foot monitor, made by the

Empire Foundry in Marysville in the 1870s, is not even the biggest. Imagine a monitor

sixteen to eighteen feet long, blasting a stream of water four hundred to five hundred

feet, like was used at Malakoff Diggings.  The gravels

were washed through sluices, and the heavy gold settled behind riffle boards. The rest of

the mountainside was washed into the streams and rivers. The gravels

were washed through sluices, and the heavy gold settled behind riffle boards. The rest of

the mountainside was washed into the streams and rivers.

At What Price?

One visitor to a massive hydraulic mining

pit observed: Nature here reminds one of a princess fallen into the hands of robbers who

cut off her fingers for the jewels she wears.

Hydraulicking may indeed have been an

efficient mining method, but at what cost to the environment? Hydraulic monitors blasted

1.5 billion cubic yards of soil and rocks from the Sierra hillsides. Imagine taking all

the soil excavated for the Panama Canal, and multiplying it times eight! Where did it all

go? It was washed through sluice boxes and dumped into the nearest creek or river canyon.

This massive amount of debris literally buried the Sierra streams, which had been teaming

with trout, salmon, and other wildlife, under one hundred feet of gravel. It changed those

natural habitats irrevocably.

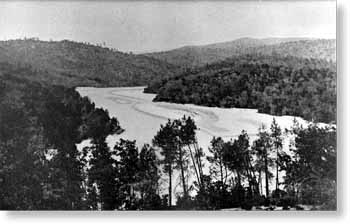

The Yuba River promptly flushed the

gravel downstream, inundating rich farmlands. Other sites, like the Bear River Canyon,

remain buried to this day. In this photo you can see a stream, partially purged of its

load of gravel, revealing the stumps of trees smothered during the initial burial.

Live and Let Live: Resume Hydraulic

Mining. It was a battle cry in the war between the hydraulic miners and the valley farmers

in the 1870s and 1880s. Massive flooding occurred in the valley orchards, grain fields,

and even towns downstream. Grain ships couldn't navigate rivers. The farmers' pleas were

ignored by the miners, because mining was king in California! The farmers organized and

fought back. Legislators debated. Dams were built to try to hold back the debris, but

nothing worked. Finally, on January 7, 1884, Judge Lorenzo Sawyer ruled on the matter. -

no more dumping of mining debris where it could reach farmlands or navigable rivers. The

farmers won. Farming became king. The rivers remained the dumping-ground for mining

debris.

Top: Hydraulic Hose, Collection of Norm Wilson

Second from Top: Hydraulic Platform, Photo by Christopher Richard

Third from Top: : Malakoff Monitors, Photo by Carlton Watkins, Collection of

Oakland Museum of California

Forth from Top: Parks Bar, Photo by G.K. Gilbert

Bottom: Shadey Creek

Dredge | Hard

Rock | Hydralic |